For one summer after graduating college, I spent occasional evenings at a local coffee shop performing walk-around magic, moving from table to table whenever I caught someone's eye who looked like they might be interested. I mostly did card work and coin sleights, but every once in a while, if it felt like a table was on board, I would do some mentalism, or "mindreading." I worked for tips, having barely convinced the night manager it was worth having me around in the first place. I'd been performing as a magician publicly sporadically since my younger sister's eighth birthday party when I was twelve, and for various reasons, that summer really needed to feel like magic was possible again.

After a few weeks of some of the most magic-dense days of my life, I stopped performing there and ended up moving from that city shortly thereafter. Six months later, I hadn't been practicing much, and I distinctly remember the feeling one night when I did some minor disappearance for friends at some party: my hands themselves felt off. The illusion worked, the Queen vanished, and people were pleased, but I felt sloppy and uncommitted doing it. A microsecond here... a tiny bit less precision there... nothing that mattered to those who I was trying to entertain, but enough for me to be displeased with my own skills. And that was a breaking point for me. I couldn't enjoy the excitement of a crowd caught up in the impossibility of matter disobeying the rules of the world when I knew the hands that helped that illusion take place were not up to snuff. I was distracted and worried that I'd botch something or let out a flash or clink, and in that slip or sound, the whole illusion would come down for us all. That night was the last time I can remember doing any magic for a crowd.

Some days I regret it. I've spent many thousands of hours—probably tens of thousands— practicing a very particular set of minute skills, movements, and mindsets, and I will never get those minutes back. Sometimes when I'm playing cards with friends, I feel the impulse to try something—mostly for the joy of trying—but I imagine I'll just disappoint myself. Oh sure, sometimes if I'm fiddling with a pack of cards by myself I play around, but performing for other people lost its joy. Until my daughter was born.

Shortly after she was three, she began to be able to possess a feeling of awe when something that clearly cannot happen happened regardless. I began to disappear things now and then, and she found that the empty air is capable of producing a number of objects... What is interesting is that as far as I can tell, she didn’t particularly associate the magic with me: it was something that was happening in the world, and she assumed it was as amazing to me as it was to her. Maybe it is. There's a particular kind of joy in watching her gasp and laugh as she closed her hands on nothing only to open them to find bits of candy and families of foam rabbits.

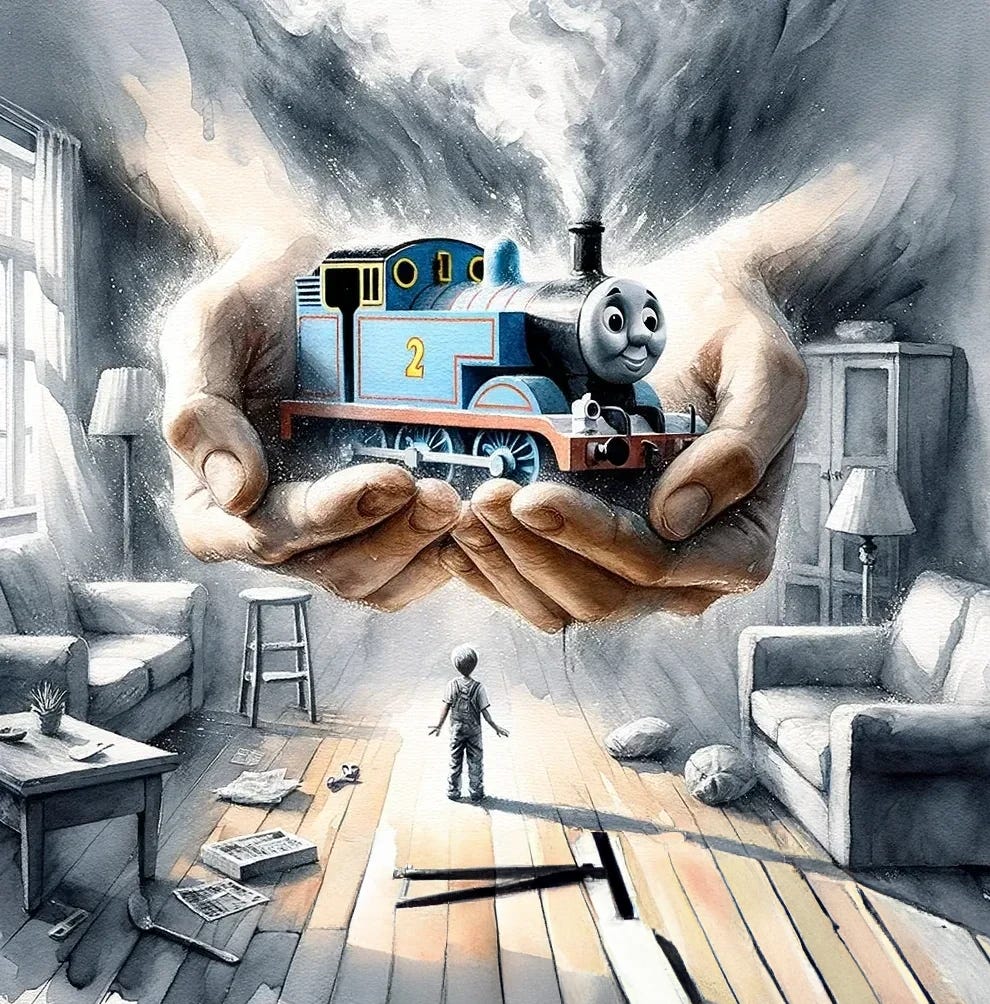

I had about a month of this joy with her when something changed. One January evening we were playing with her trains when one of them disappeared after I ran my hands over it.

She laughed, squealing "Where did it go, Papa!?!," and began to charge around the room to see which chair or couch had snatched away her toy. And then she stopped.

In a moment of inspiration, she turned to me triumphantly and said, "I know! I'll make it come back!" Setting herself down deliberately, she flourished her hands magically... and—in what I thought was a moment of paternal genius—the train appeared in my hands exactly as she finished her arcane, toddler gesticulation.

It was then she began to cry. She hadn't seen the train reappear. "Papa..." she sobbed, "my magic doesn't work right..." I showed her that the train had reappeared in my hands, but she wasn't interested... She gestured again, and again whatever it was that she envisioned happening didn't happen.

"Sweetie," I said, "look here and see my hands. The train's right here."

My attempts to calm her failed as she built up to a shriek. "But it's not doing what I want!!!"

As her tears and volume grew, all attempts to soothe her were worthless until my wife came in from the other room to see what damage I had done. As she walked past me, I told her that our daughter had just discovered magic isn't real.

But that isn't quite right. It isn't that magic isn't real. It's that magic was never supposed to be the point in the first place: awe was. Awe, and the laugh that erupts when the impossible takes place right in front of you. In your own hands. It's about knowing it is impossible, and feeling it there in front of you regardless.

And so when Nahar is older—perhaps when she is grown—I'm going to tell her this story, and then together we'll see if we can't find Thomas.