Re-making Memory

How Things Are

Dave Harrity is a poet and a great friend. More particularly, he’s a great friend to me. I have other friends too, but Dave is the only one who asks me how “the writing is going” and really wants to know. That is, he doesn’t really mean “how much further are you towards the next book?” Or “what was your day like while you were writing?” He actually wants to know what it feels like for me to write.

He once told me that he really appreciated how well I could explain things, but that when I was writing poetry he’d encourage me to break that habit and let the poem speak for itself. A poem does not need explanation and certainly not within the poem.

Years spent writing mostly academic work had gotten me into a useful habit there that wasn’t serving me elsewhere. Often the skills that help us survive in one place are not the ones we need to thrive in others.

Months later when I had Dave read a batch of new poems he gave me the note that “vagueness isn’t the same as breaking the habit of explaining.” Which is right. It is hard to allow something to be what it is in general. Even more so when what we are trying to do is intensify what a thing is via a poem. It is challenging to be precise and not succumb to the need to say why that precision matters. That’s how I think of poems by the way: distilled moments turned into text.

I heard an interview recently with Karim Nader, a neuroscientist that works at McGill University in Montreal. He studies memory. He told a story about a woman that had had a very bad experience as a child. When she told her mother, her mother accused her of making up stories. For years, she never spoke of it to anyone, not even her husband. She would get undressed in the dark, as if hiding from her past.

But then Nader and his team tried something new. They gave her a drug while she revisited the trauma in her mind. A week later, something had shifted. The memory was still there, but its sharp edges had been sanded down. The overwhelming emotion that once held her captive had loosened its grip. She felt like herself again. Like she had been given back to herself.

The drug they used had previously been shown to prevent memories from being formed in the first place. Which by itself is pretty amazing. But they’ve since shown that it appears it can be used to interrupt and fade memories that already exist. As the memory is being recalled they administer this drug and “abolished the emotional enhancement of memory and made emotional memories comparable to neutral memories.” They could reduce the feelings of horror and shame attached to a moment in time without removing the memory itself. The drug used to “erase a memory” as it was being formed is able to do the same later, when it was being remembered.

As I listened to Nader, I couldn't help but feel a twinge of unease. Is it right, I wondered, to tinker with the very stuff that makes us who we are? Our memories, painful as they may be, are the threads that weave the tapestry of our identity. I know that cognition isn’t the only thing I think that a person is, but I certainly feel like part of who I am is the sum of my remembering.

But then I thought of the woman, undressing in the light for the first time in years. Naked and unafraid.

Some believe that memories are like precious artifacts, stored away in some untouchable vault deep within the recesses of our minds. Each one a perfect, immutable replica of a moment gone by, able to be retrieved and relived with clarity. But increasingly we are learning this metaphor leads us away from what is actually the case.

Every time we dive into our past, we are not simply retrieving a file from a neatly organized cabinet. No. Remembering itself is an act of creation, of imagination. We are rebuilding the memory anew, shaping it — whether we like it or not — by the sharp edge of our present perspectives and understanding.

The memory of my childhood summer is not the same at 20 as it will be at 60. Memory is remade by every remembering. Our most cherished memories may be more a reflection of who we are now than a record of who we were then, shaped by the lens of our present longings. The things we hold on to the most come to resemble that holding. And the things we fear that terror. We remember our own sense of things, not the things themselves.

The trick, then, as a poet, is, yes, to let things be themselves on the page. But also to make sure that the hands that placed them there leave a trace. Leave the page warm.

How Things Are

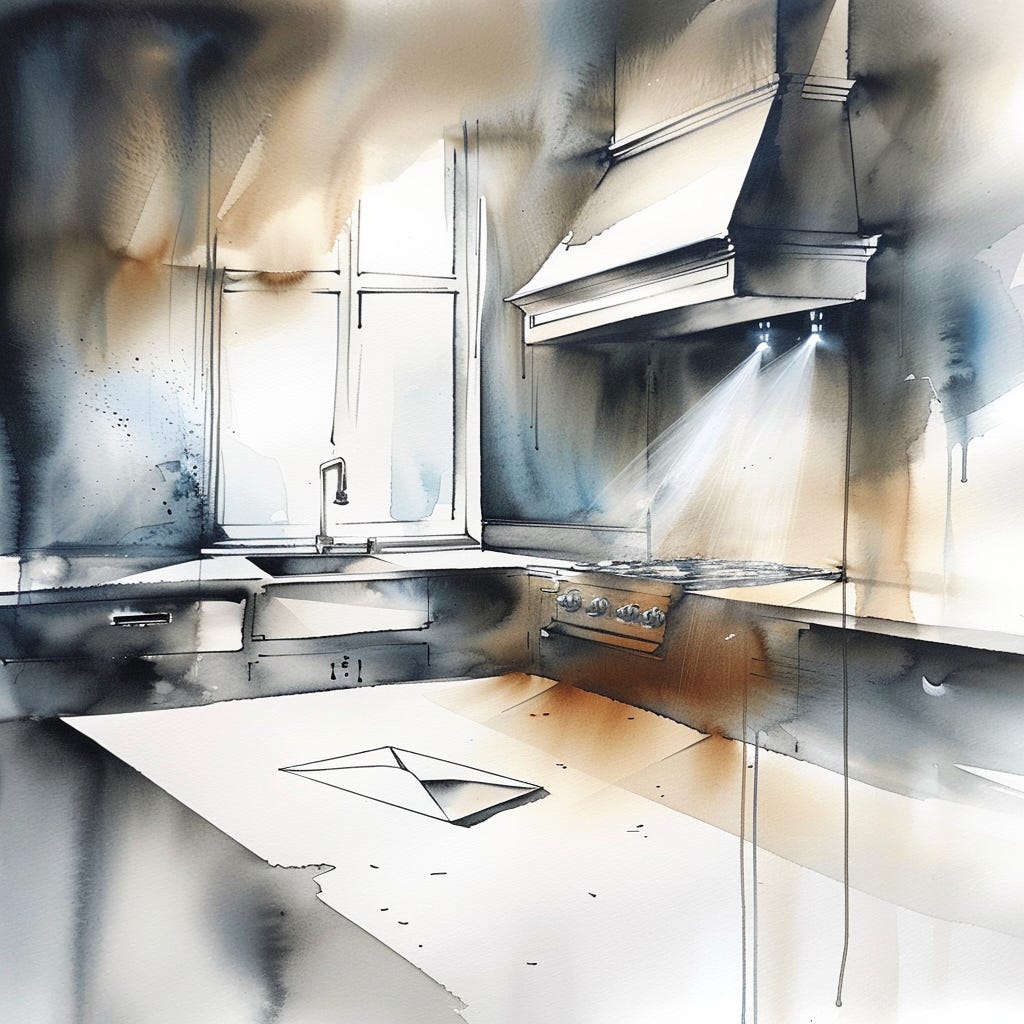

When I was in college I sent my mother a letter and never received a reply. So I am left to create the scene myself: When she pulled over to get the mail, she was in her 2004 Dodge minivan, salt-worn. Its odometer evidence: an enduring devotion to travel soccer and band practices. By the time she arrived at her kitchen table to open the envelope, she buzzed with wonder. It was a thank-you note from her nearly-grown son. I know I don’t write much, but I just remembered a time when I was a kid and you were younger, and it was just us on a walk in the neighborhood. I remembered asking you how long it took to walk a whole mile and you said, without hesitation, “20 minutes.” I’ve been using that same number for years Mom, but I just today recalled the color of the grass when you gave it to me; the sound of your bare feet on pavement; what it felt like to be the son of someone so smart. Thank you. She cried; of course she cried. And she also fumbled to find a response. She never replied. I recently found the letter, tucked inside yellowed bills and government records. I could have sworn I had sent it.